On January 19, 1787 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart experienced perhaps the most triumphant evening of his life. What had happened?

What you will read in this article:

Mozart in Prague

Mozart loved the people of Prague, and the people of Prague loved Mozart. This intimate relationship began on a winter evening in 1787. Mozart had traveled to Prague for the first time to conduct his latest opera – “The Marriage of Figaro” – at the Estates Theater (the Estates Theater was then called the “Count Nostitz’s National Theater”. If you want to know more about the history of this house, read my article about the Prague Estates Theater).

In Mozart’s time, the concept of musician was universal. Anyone who was a musician composed, conducted and was a virtuoso on at least one instrument (with one famous exception: Joseph Haydn was perhaps the only composer of this epoch who was not also a virtuoso). It is therefore not surprising that Mozart organized a so-called “Akademie” – the then common term for extensive concert events – also in the National Theater between two days of performances of Figaro. This 19 January 1787 was to be the most triumphant evening of his life.

Former "akademie" and today's "concert" have little in common

Today we can hardly imagine the temporal extent and the heterogeneity of the program of an “Akademie” in the 18th century. These concert events often lasted four, five, six or even more hours; music of all “genres” was performed, from piano sonatas to chamber music, opera arias and symphonies. One could say that they were crossovers in the best modern sense of the word.

However, one crucial thing was different back then: almost everything that was played was brand new. The hunger for music in society at that time was probably comparable to that of today, with the difference that neither Spotify nor ITunes were available to satisfy this hunger.

In the course of the Akademie on January 19, 1787, Mozart presented himself mainly as a pianist, performing his own compositions on the piano. The audience’s benevolence was probably already on his side; this benevolence, however, turned into open enthusiasm when Mozart improvised for half an hour without interruption at the end of the event.

Improvisation as an important part of musical education

Mozart was an excellent improviser. At this point it is important to stress that this ability has little to do with the term “genius”, which especially often is used for Mozart. The musical education at that time was based on the teaching of so-called “Satzmodelle” (we would say “patterns” today), which, practiced from early childhood on, became second nature to the musician.

The Satzmodelle could be combined and expanded; together with the complete absorption of the formal ideas of the time and a high technical level in the mastery of an instrument, this may have resulted in improvisational achievements that are unimaginable for us today (even long after Mozart’s death it was still common practice to be able to improvise complicated genres such as fugues (just imagine!). The Bach family is known to have improvised “quodlibets” by singing them at lunch – this involves superimposing several independent melodies, such as folk songs, on top of each other. If you try to sing “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” and “Yankee Doodle” at the same time at your next family celebration, you will realize what an achievement this is. Perhaps you would rather like to start with simple song accompaniment).

Mozart, the pianist vs. Mozart, the symphonist

Back to 19 January 1787: The enthusiasm of the Prague audience must have been overwhelming. After multiple standing ovations, Mozart felt compelled to sit down at the instrument again and bring the evening to a glittering conclusion with two further improvisations. In view of such an eventful evening, the report of the Prague Oberpostamtszeitung of January 23, 1787 appears rather plain:

“On Friday the 19th, Mr. Mozart gave a concert on the fortepiano in the local National Theater. Everything that one could expect from this great artist, he completely fulfilled.

And yet this short note indirectly reflects the overwhelming of the audience (and, obviously, the critics), since it describes Mozart exclusively in his function as a pianist. The fact that Mozart’s newest symphonic creation, the Symphony in D Major, KV 504, also received its premiere at the same Akademie was completely ignored by the press.

Harmonic shocks in the first movement of the symphony KV 504

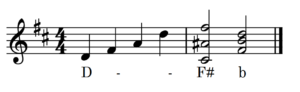

This cannot be due to the musical content of the symphony itself: even the beginning of the slow introduction of the first movement must have had a shocking effect on the tonally trained ear, which we may ascribe to the audience at the time. An F sharp major chord suddenly bursts in forte in the fourth bar and leads to B minor, from where the introduction needs 32 bars to reach the dominant of the actual key D major via harmonically widely branching paths.

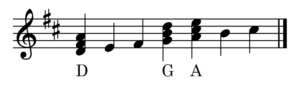

Take a short trip with me into the world of music theory to understand what this means. If you have read my article on simple song accompaniment, you know that the three main harmonies of a key can be used to accompany almost any song. In D major, the key of the symphony KV 504, the main harmonies are D major, G major and A major:

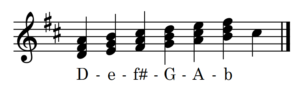

Now there are also the secondary harmonies; in D major these are E minor, F sharp minor and B minor:

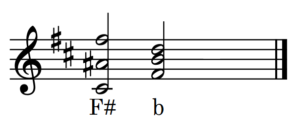

You can reach each of these secondary harmonies by inserting a so-called “secondary dominant”. If you want to reach the secondary harmony B minor, you need F sharp major as the secondary dominant:

This does not sound exciting in itself. But if you let this turn “burst” into a D major context completely unexpectedly, the effect is quite different – and that is exactly what Mozart does:

Nowadays, our hearing is hardly sensitive to such harmonic turns; the hair of the Mozart audience may have stood on end.

I had the pleasure of conducting a performance of Mozart’s Symphony in D Major KV 504 with the Vienna Chamber Orchestra. Here you can see and hear the first three minutes of the performance, which also contain the harmonic twist described above (from 0:17):

Recording of June 17, 2019 from the Radiokulturhaus Vienna.

Orchestra: Vienna Chamber Orchestra

Conductor: Jonathan Stark

Syncopations in the first movement of KV 504

After the slow introduction, Mozart surprises us with the predominance of syncopated rhythm. If this term is new to you, read my article about syncopation. There, together with Adrian, the Music Theory MentOWL, I explained the syncopated effect of extended notes, but this is a different kind of syncope. Mozart “shifts” the notes by the value of an eighth, so that they always end up between the accents of the bar – creating first-class “off-beat” music:

In the original it sounds like this:

Recording of June 17, 2019 from the Radiokulturhaus Vienna.

Orchestra: Vienna Chamber Orchestra

Conductor: Jonathan Stark

The syncopated rhythm dominates the entire first movement of the Symphony in D major, K. 504, which later, appropriately, was given the nickname “Prague” Symphony. I hope you enjoy watching and listening to the concert recording of June 17, 2019:

Recording of June 17, 2019 from the Radiokulturhaus Vienna.

Orchestra: Vienna Chamber Orchestra

Conductor: Jonathan Stark

Jonathan Stark – Conductor

Hello! I'm Jonathan Stark. As a conductor, it is important to me that visits to concerts and operas leave a lasting impression on the audience. Background knowledge helps to achieve this. That's why I blog here about key works of classical music, about composers, about opera and much more that happens in the exciting world of music.

Hallo Jonathan, sehr interessant für mich, diese Mozart – Symphony mit der Kenntnis deiner Aspekte an zu hören.