With the help of the doctrine of affects, emotions were triggered in the listeners in the Baroque and Classical eras. This was achieved thanks to precise musical tools. What exactly the doctrine of affects was, which affects were triggered with music and which clever people wrote about it, you can read below.

What you will read in this article:

Doctrine of affects: a definition

An affect is a mental sensation or an emotion. The decisive factor is that the cause of this emotion lies outside the individual who feels this emotion. Thus, the affect must be triggered from outside.

Behind the doctrine of affects was the idea that music can be such a trigger for affect. A definition of the doctrine of affects could therefore be as follows:

The doctrine of affects is the production of emotions ("affects") by musical means.

What are the affects in the doctrine of affects?

Now you could stop for a moment and think about what repertoire of emotions you yourself have. Surely you have been angry and sad, but also happy and perhaps euphoric.

With this, you actually already know the most important affects. The theorists of the musical theory of affects were in agreement about the types of affects. The only differences are the subdivisions of the affects, which became more and more numerous in the course of time. In the following, I would like to show you which affects three of the most important theorists of the doctrine of affects have defined:

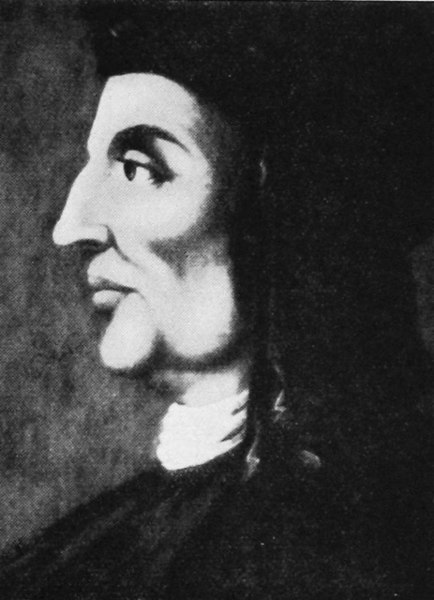

1. Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680) was a German polymath. He spent most of his life conducting research at the Collegium Romanum in Rome. In 1650, Kircher named eight affects that could be triggered by music: Love, Sadness, Joy, Anger, Pity, Fear, Courage, and Despair.

2. Johann Mattheson

Johann Mattheson (1681-1764) was a German opera singer, composer, music writer and patron. He was also a longtime friend of George Frideric Handel. Mattheson added six more to Kircher’s affects in 1739: Pride, Humility, Hope, Desire, Obstinacy and Jealousy.

3. Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg

Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg (1718-1795) was a German music theorist, music critic and music historian. He is credited with the first systematization and canonization of the doctrine of affects. In it, an expansion is undertaken again, so that Marpurg speaks of 27 (!) different affects.

How are affects expressed musically?

Now you may ask yourself how these affects are to be generated by musical means. In general, in the doctrine of affects, it was assumed that almost all musical parameters can be triggers of affect. However, some parameters were preferred.

Primary and secondary affect triggers in music

From the theoretical writings of the Baroque period, a rough dichotomy can be derived that indicates how significant a musical parameter is for the doctrine of affects. The parameters that convey an affect particularly well (the “primary affect triggers”) are the following:

Melody

The melody is a string of intervals (intervals of tones). Each interval had a particular affect associated with it. (If you are not yet familiar with the concept of intervals, read this article by Earmaster).

Rhythm

The rhythm was considered inseparable from the melody and also decisively shaped the affect of a musical passage.

Key

This is a really big area. The aspect of the key, with regard to the doctrine of affects, was related to the the concept of characteristics of key signatures, which was decisive for entire generations of composers. (If you want to get an overview of the different characteristics of the individual keys, read this article).

Harmony

Harmonics also played a crucial role in the doctrine of affects, because depending on how “sharp” or “mild” the harmonic progression of a piece was, a different affect was triggered.

In addition to these primary affect triggers, however, there were other musical parameters that could also trigger affects according to the doctrine of affects. These “secondary affect triggers” include:

Time signature

The time signature determines the focal points of the music, and thus the affect. (If you want to learn more about the focal points in a piece of music, read on here).

Tempo

You may be surprised that this aspect has only just come up. In fact, a certain tempo per se does not stand for a specific affect. A slow piece, for example, can be both sad and solemnly majestic. (Read more about tempo here or learn what Mozart had to say about tempo).

Timbre

This aspect could be equated with the choice of instrument in the period in which the doctrine of affects was developed. Depending on which instrument played a certain passage, the affect of that passage could be changed.

Playing technique

String instruments, for example, can be bowed or plucked – the transported affect is different in each case.

Now you know the main affect triggers in the doctrine of affects. In the following, I would like to present to you what two prominent representatives of the doctrine of affects had to say on this subject: Gioseffo Zarlino and Johann Mattheson.

Zarlino: Doctrine of affects in detail

Gioseffo Zarlino (1517-1590) was an Italian conductor, music theorist and composer. He was primarily active at the famous St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice.

As an important music theorist of his time, he also had important contributions to make to the doctrine of affects. His meticulous approach is particularly noteworthy here: Zarlino advocated that the doctrine of affects should work down to the smallest building blocks of music (the intervals or intervals between notes). Thus, he defined intervals that stood for sad affects (for example, the minor third and the minor sixth), and intervals that stood for joyful affects (for example, the major second and the major third). In addition, according to Zarlino’s doctrine of affects, the direction of the interval (upward or downward) also had an influence on the affect that was triggered.

Mattheson: the forefather of the doctrine of affects

I have already briefly mentioned Johann Mattheson above. Mattheson is still important for conductors today because his main work “Der vollkommene Capellmeister” is still considered a standard work of historical performance practice.

For Mattheson, it was absolutely essential that music should always convey concrete affects. He also described in detail how exactly this should happen. Therefore, I would like to let Mr. Mattheson speak for himself:

Hope is an elevation of the soul or spirits; but despair is a depression of this: all of which are things which can very naturally be represented with sound, especially when the other circumscances (tempo in particular) contribute their part. And in this way one can form a sensitive concept of all the emotions and compose accordingly

Johann Mattheson

Anger, ardor, vengeance, rage, fury, and all other such violent affections, are actually far better at making available all sorts of musical inventions than the gentle and pleasant passions which are handled with much more refinement. Yet it is also not enough with the former if one only rumbles along strongly, makes a lot of noise and boldly rages: notes with many tails will simply not suffice, as many think; but each of these violent qualities requires its own particular characteristics, and, despite forceful expression, must still have a becoming singing quality: as our general principle, which we must not lose sight of, expressly demands.

Johann Mattheson

And later on?

Now you have received an overview of the doctrine of affects. But what happened next with this important concept? In the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, the doctrine of affects was increasingly supplanted by the idea of musical “character.” This also had to do with the increasing focus on the artist as an individual.

Think about it: a “character” unites many different affects in itself, which can sometimes come to the fore more strongly, sometimes more weakly. But the character always remains the same. Thus, starting from the doctrine of affects, a line of development can be drawn to the romantic character piece.

Jonathan Stark – Conductor

Hello! I'm Jonathan Stark. As a conductor, it is important to me that visits to concerts and operas leave a lasting impression on the audience. Background knowledge helps to achieve this. That's why I blog here about key works of classical music, about composers, about opera and much more that happens in the exciting world of music.