Tempo is a significant factor in music. It is more influential in shaping the effect of a piece of music than almost any other aspect. In this article, you will learn everything about tempo in music, step by step. By the end, you will be able to understand any tempo indication.

What you will read in this article:

Tempo (music) – what is that?

First of all, it is necessary to clarify what tempo in music is all about.

Tempo (from Italian: "time") in music indicates how fast a piece of music should be played.

Short definition of tempo in music

Now you may ask: why does a tempo actually need to be specified? Isn’t it enough to write down the music in notes?

Good questions. They point to a “problem” with our notation.

The problem of our musical notation

Our present musical notation has proven itself. It translates an acoustic process into the visual. That’s a daunting task, and measured against that, our notation does a pretty good job. It is not perfect, however, because information is lost in the transfer. Example:

Here you can see a simple musical rhythm, consisting of half notes (𝅗𝅥) and quarter notes (𝅘𝅥). Half notes, by definition, last twice as long as quarter notes. So the second note in the example must be sustained twice as long as the third note.

But: the notation does not convey any information about the absolute length of the notes.

You could sustain the half note for two seconds and the quarter note for one second. Good.

But you could also sustain the half note for ten years and the quarter note for five years.

Both would correspond to the above example and would be correct, because today’s notation can only represent relative rhythmic values, not absolute durations.

Therefore, one has to decide on a certain tempo.

The question of the "right tempo" in the course of music history

This question of the “right tempo” was raised early in music history and is still hotly debated today. The way in which the decision for a certain tempo was made has changed again and again in the course of music history.

Until about 1750: Choosing tempo without tempo indication

Until about 1750, it was unusual to add a tempo indication to the musical text. The musicians could “see” in a piece of music in which tempo it should be played. The tempo was determined by factors such as time signature, note values, harmonic rhythm and the character of the piece.

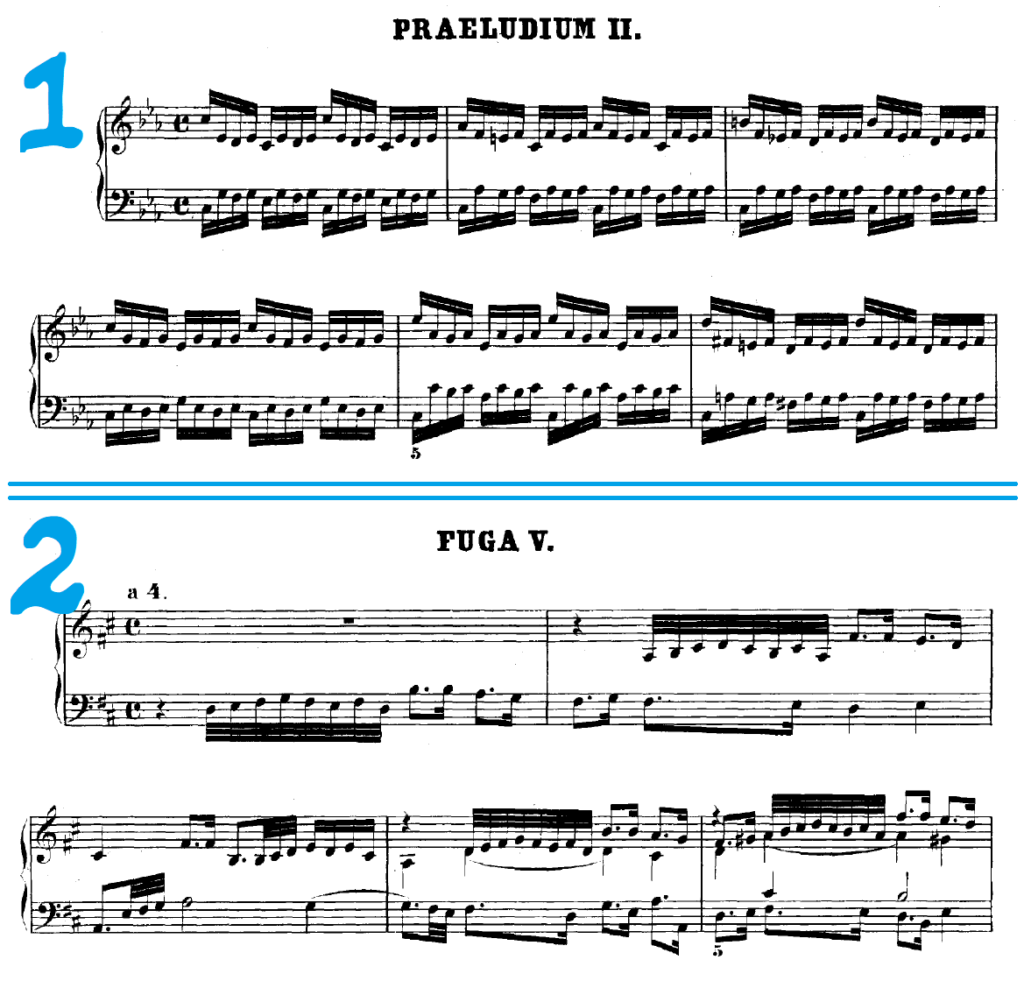

Here you can see two pieces from Johann Sebastian Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier:

For Bach and his contemporaries, it was clear that the first piece had to be played at a faster tempo than the second piece. The note values are the crucial clue: in the first piece sixteenth notes are the smallest rhythmic unit, in the second piece thirty-second notes.

So in the second piece you have to fit twice as many notes on one beat as in the first piece. The second piece must therefore be played in a slower pulse (= a slower tempo).

Exactly how fast or slow is left open. There is room for interpretation here. Only later were more precise tempo indications made.

From about 1750: Tempo = tempo word + time signature

From about 1750 on, an elaborate system was used to clarify the tempo of a piece of music. Let’s look at this using Mozart’s Prague Symphony as an example. Here is the beginning (Viennese Chamber Orchestra, Jonathan Stark (conductor):

Mozart combines a time signature with a tempo word. The time signature c stands for a four-four time signature, and the tempo word Adagio is Italian and means “slow”.

There are many tempo words in music. There are also different names for gradual changes in tempo: For example, you can say “faster” in 27 different ways and “slower” in 30 different ways.

So Mozart only needs a few strokes of ink to shout to me, the conductor, over 200 years apart, “Take slow quarters!” How slow, exactly? Well, I get to decide that. With my baton, I communicate my decision to the orchestra.

This system for indicating tempo (tempo = tempo word + time signature) was so useful that people soon asked themselves: can’t we use the tempo indication to convey even more information?

Born was the character word.

Even more info in a small space: tempo = tempo word + character word + time signature

Soon the tempo indication was used to also indicate the character of the music. This was expressed in a character word added to the tempo word. Here are a few examples of character words:

| con dolore | with pain |

| con fuoco | with fire |

| espressivo | expressive |

| grazioso | graceful |

| molto | very |

“Adagio con dolore” would be “Slow, with pain”, “Presto con fuoco” would be “Fast, with fire”. Thus, by combining, one could already craft quite precise tempo indications.

But that was not nearly precise enough. The development continued.

Precision first! Specifying musical tempos with the metronome

From about 1800 on, the system of tempo indication (tempo = tempo word + character word + time signature) was no longer precise enough for musicians. Tempi should be indicated in such a way that they could be understood everywhere without misunderstandings. So scholars all over Europe set to work.

In the years 1814/1815, a device was developed with which musical tempos could be precisely indicated: The metronome! The genesis of the metronome is a veritable musical thriller: the two inventors Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel and Johann Nepomuk Mälzel fought a legal battle over who owned the rights to the metronome.

You can read about this musical thriller in the Summer 2022 Mini-Experience.

A metronome emits a certain number of acoustic pulses at regular intervals per minute. This number of pulses is combined with a specific note value. For example, the metronome specification ♩ = 120 means that a quarter note is exactly as long as an impulse if the metronome emits 120 pulses per minute (i.e., half a second).

The metronome thus made it possible to specify the tempo in music precisely from 1815 onward. This does not mean, however, that from that point on, tempo was prescribed only in metronome indications. Rather, all the systems you have encountered so far existed side by side (and continue to do so to this day).

I think that’s a good thing. Metronome indications are useful, but sometimes it makes sense to switch to a tempo word that leaves room for interpretation. Which solution is chosen depends on the composer. An extreme example is certainly the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007), who even used metronome indications with decimal places.

Here is an overview of which tempo words correspond approximately to which metronome markings (from slow to fast, according to Mälzel 1816):

| Tempo Word | Metronome Marking |

|---|---|

| Largo/Lento | 40–60 |

| Larghetto | 60–66 |

| Adagio | 66–76 |

| Andante | 76–108 |

| Moderato | 108–120 |

| Allegro | 120–168 |

| Presto/Allegro assai | 168–200 |

| Prestissimo | 200–208 |

And now all together! The "recipe" for tempo indications in music

Now that you’ve learned about the different systems, you can not only understand all the tempo indications in music, but also craft your own. Help yourself from the tables on tempo words, character words and metronome indications and put together the individual components, for example:

- Lento con dolore 𝅘𝅥 = 40

- Andante grazioso 𝅘𝅥 = 96

- Prestissimo con fuoco 𝅗𝅥 = 208

Have fun trying it out! 😊

Jonathan Stark – Conductor

Hello! I'm Jonathan Stark. As a conductor, it is important to me that visits to concerts and operas leave a lasting impression on the audience. Background knowledge helps to achieve this. That's why I blog here about key works of classical music, about composers, about opera and much more that happens in the exciting world of music.

Habe viel dazu gelernt in “Tempo (Musik) “.

Herzlichen Dank für die vielen Infos.

Das freut mich! 🙂